Laurence Barker couching a sheet of paper with students in the Printmaking Department at Cranbrook Academy of Art, 1963. AA3030-21. Courtesy Cranbrook Archives, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan.

In the broadest of brush strokes: after approximately 35 years of living in Barcelona, Spain, I returned to the United States in February 2007 where I since divide my time between Odessa, Texas where my daughter Mercedes lives, and Bloomfield Hills, Michigan where someone else lives. (Not to go all treacly, but more fulsomely expressed, “…where Someone Else lives.”)

I appear to have come full circle for I now live directly in front of the en- trance to Cranbrook Academy of Art on Woodward Avenue. In the late 1920s George Booth, a Detroit newspaper baron and philanthropist, commissioned the Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen to design a community of educational institutions which he accomplished with the help of artists, craftsmen, and student apprentices. This marked the informal beginning of the Academy which was officially sanctioned in 1932 with Saarinen as its first president. My tenure there in the Printmaking Department coincided exactly with the decade of the sixties, at the end of which, in 1970, I left for Spain.

My re-introduction to the Academy a few years ago—that is, to the quality and even greater adventurousness of student art in these times—occurred while thumbing through the school catalog backwards. It was highly instruc- tive. The normal left-to-right sequence of the department overview followed by examples of student work was reversed. I was often hard pressed to guess from which department the art proceeded. For instance, there were paintings from the Architecture Department (surprise!), cloth sculpture from Metal- smithing, and many examples of mixed-media constructions throughout the departments. With traditional craft boundaries crumbling, if not already quite demolished, the interdisciplinary imprimatur was unmistakable.

It has been slowly dawning on me that, apart from sporadic lecturing, I have been completely out of the university loop for ages. Out and away, I mean. When I departed for Spain I became de-institutionalized; I essentially left all academic concerns behind me. And although Barcelona resembles the Catskill Mountains not in the least, like Rip Van Winkle who slept for twenty years, I too have been unaware—out of it, in the vernacular—of the many changes that have taken place in art schools, and for many more years than twenty.

My one and only visit to the Printmaking Department at Cranbrook since leaving in 1970 occurred ten years later in 1980 when I participated in a printmaking symposium. The studios on that occasion were buzzing with activity all across the board: etching, lithography, silkscreen, and relief printing. Twenty-odd years later all the printing presses—or so I have been told—were unceremo- niously stored in a corner of the department’s basement. Like so much superfluous luggage from the era of steamship travel tagged for the ship’s hold, they were “Not Wanted on Voyage.”

How to account for this peculiar abandonment? Beyond the strong suspicion of Deep Thought run amok, I would not care to speculate. If not essentially ink on paper—bedrock basic, one might rashly suppose—what else can printmaking be about? Evi- dently it was about something altogether different, in which case surely then the activity in question deserved another and more ap- propriate name. Whatever the explanation, to the rescue came Ran- dy Bolton, Artist-in-Residence (in oldspeak, Department Head), who restored much-needed order and balance and runs a wonder- ful department. In the early months of my return he kindly gave me a tour of the Print Media Department.

The Print Media Department? When did that happen? What be- came of Printmaking? Well I might rub my eyes. But, of course, the modern world happened: the computer, digital photography, and video happened; flatbed scanners—now a fixture in every depart- ment’s tool kit—happened. It is as easy to imagine a world without masking tape as it is to contemplate doing without today’s techno- logical advancements.

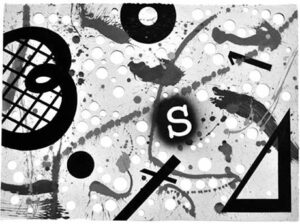

Thus university art departments and art schools have incorpo- rated new technology into their respective programs. Printmaking is no exception: etching, relief printing, and stone lithography have had to make room for computer-generated imagery and its repro- duction. Not elimination of the old, but, rather, accommodation of the new is the sensible rationale. Print Media—aptly named as it turns out—bespeaks this enlarged, more inclusive vision.

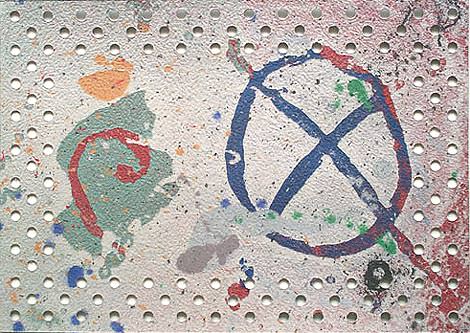

As we progressed through the studios on the tour, I came upon a student—be still, my foolish heart—making a piece of pulp art not ten feet from where we made paper in the sixties. It was a confounding moment; it was also, however convoluted, a Planet- of-the-Apes moment. Unlike Charlton Heston, who had to wait until the last reel to discover where his spaceship had landed, I always knew what “planet” I was on—one, alas, long since barren of papermaking—and yet, contrary to all expectations, here was a bloom! Call it ad hoc papermaking: a bucket of water, cotton lint- ers, and a hydropulper. Here today, gone tomorrow.

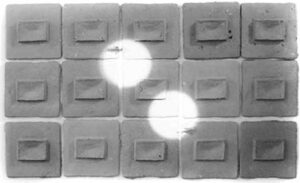

In this year’s student exhibition there was another example of under-the-radar papermaking. Kimberly Counes, a student in the 2D Design Department, presented a mixed-media piece com- prised of cast paper, video, and animation—a rather unusual and intriguing combination of elements. Counes told me she burned up half a dozen kitchen blenders macerating pages of the New York Times and other prominent national newspapers to form fifteen (very gray) castings measuring 18 inches square with a raised cen- ter. Mounted in three horizontal rows of five pieces each, a cluster of projectors from the ceiling directed video and animation to the areas of high relief in the center of each paper casting.

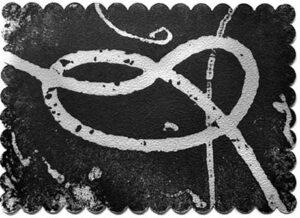

The principle lesson I deduce from these two examples is sim- ply this: if an artist wants expressive paper she has to make it her- self, and—with or without benefit of a formal program—she will. The paper may have a rough and primitive feel to it perhaps, but it is this very quality that is often sought to provide desired contrast. In Counes’ work, for example, the cast paper is the counter note to the immateriality of the light and shadows of the video. Low and high technologies joined at the hip; in this way old and new can form odd and arresting juxtapositions. Similarly, some of us in the sixties were printing photolithographs on shaped handmade paper which gave a distinctly different and unexpected look that slowed down the viewing.

Although paper will forever be intimately linked with books and prints—it being nothing less than the prime vehicle of the last two thousand years of human knowledge and culture—from a fine arts perspective, it has since outgrown that exclusive domain and, in addition, has become a stand-alone art medium in its own right. After my seminar with Douglass Howell in the summer of 1962, my interest and purpose, logically enough, was to provide paper for Cranbrook’s Printmaking Department. But in the fol- lowing years the whole development of paper art—art that is ini- tially designed at the vat level—became the work of many artists from a variety of disciplines.

In a 1988 Hand Papermaking interview with John Gerard, I said that you would have needed a crystal ball to see how reason- able it would have been to make hand papermaking a service area available to everyone from the very beginning. Although possi- bly a head-scratching, polemical idea at the time, I think it makes even more sense today. I would almost equate such a program with the comparable utility of an all-purpose woodshop.

The wide appeal of paper, whether as substrate or independent medium, justifies, in my opinion, this service area concept—a kind of Peaceable Kingdom where students with diverging inter- ests find common purpose in the making of pulp. There will be those who will want to make sheets of paper in an appropriately equipped facility and others who will want to drag it off to their studios for who-knows-what imaginative ends.

The spirit, if not always the letter, of the admittedly thin gruel of a syllabus I followed in the sixties might be summed up sche- matically as follows: teach students papermaking on Day One and turn them loose on Day Two. Not nearly so heartless as it might appear, this bracing formulation underscores the rapid indepen- dence gained from but a brief orientation. We would beat rag to pulp in the morning and form and press sheets of paper in the af- ternoon. At the end of the day we had essentially gone through the whole papermaking cycle in lockstep. After the students learned.

the basic management of the Hollander beater, greater understand- ing and refinement of technique would come with subsequent practice and exposure to a variety of fibers and textiles.

Similarly a common papermaking studio would offer like instruction and supervision to all interested students. Not to mini- mize the practical difficulties, but the implementation of such a papermaking program would broadly enrich the curriculum of any art school or university, from sea to shining sea.